What’s in a Continuation

Many people have heard the word “continuation” because it has something to do with node’s callback hell. I don’t think most people understand what continuations really are, though. They aren’t just a callback function used by async functions.

A continuation is a representation of the control flow of your program at any point in time, essentially the stack. In abstract terms, it represents "the rest of your program." In languages like Scheme that expose continuations as first-class values, you can capture the current continuation and invoke it later. When invoked, the current program state is replaced with the state at which the continuation was captured (i.e. the current stack is replaced with the stack from the continuation).

Continuations allow you to literally "jump" to different places in your code. They are a low-level primitive that gives you control over execution flow, allowing you implement everything from resumable exceptions to coroutines. Understanding continuations was the best thing I did as a young programmer; it forces you to understand how control flow works.

It would be neat to see something like continuations implemented in JavaScript engines because you can implement everything on top of them (note that I said something like, as continuations themselves are very hard to optimize). I'm a fan of low-level primitives for the same reasons as the Extensible Web Manifesto: let users evolve the language over time.

I recently ended up implementing continuations in JavaScript. It wasn’t on purpose; I was originally pursuing a way to arbitrarily pause JavaScript in user-land so I could write tutorials and interactive editors. I realized that to arbitrarily pause JS, I would need all the machinery necessary for continuations. The ability to save a stack and resume it later. Eventually I discovered the paper "Exceptional Continuations in JavaScript" and was able to achieve my in-browser stepping debugger by implementing continuations.

I wrote more about the backstory of my work at the end of this post. I did most of this work 2 years ago and I'm now polishing it up and publishing it.

function foo(x) { console.log(x); if (x <= 0) { return x; } else { return x + foo(x - 1); }}function main() { console.log(foo(3));}main();Output:

Stack:

And just like that, I realized that I could expose continuations first-class to this special variant of JS, which is way more interesting than my stepping debugger. In this article, I will use my work to explain what continuations are and give you a chance to interact with them.

I will explain how it is implemented in the next post. A short version: it transforms all code into a state machine and uses exceptions to save the state of all functions on the stack. This means that every function is transformed into a big switch statement with every expression as separate cases, giving us the ability to arbitrarily jump around.

This transform is very similar to what regenerator does, which compiles JavaScript generators to ES5 code. In fact, that project is what motivated this work. Two years ago, I forked regenerator and implemented everything you see here. That means that it doesn't support a lot of recent ES6 features and it's missing a lot of bug fixes.

Visit the Unwinder repo to see the code and try it yourself. Warning: this is very prototype quality and many things are ugly. There's a very good chance that you will hit bugs. However, with some polish work this has a chance to become a place where we can explore interesting patterns.

A few other caveats:

You cannot step through native frames, or use continuations when they are on the stack. If you use the native array

forEachand capture the continuation in the callback, things will go badly. This requires all code to be compiled through this transformer if you want to use continuations (normal code can call out to native code just fine, however).This technique favors performance of code that does not use continuations. Capturing continuations is not very fast, but if you are implementing something like a debugger, that doesn't matter. However, if you are implementing advanced control flow operators, you will likely hit performance problems. This is a good place to experiment with them though.

Introducing Continuations

Let's revisit the definition of a continuation: wikipedia describes it as "an abstract representation of the control state of a computer program. A continuation reifies the program control state…" The key words are control state. This means that when a continuation is created, it contains all the necessary information to resume the program exactly at the point in time which is was created.

This is how the stepping debugger works internally. The generated code looks for breakpoints, and when one is hit, it captures the current continuation and stops executing. Resuming is as simple as invoking the saved continuation.

Let's have some real fun though and expose continuations as first-class values! In Scheme, you use call-with-current-continuation to capture the current continuation, or the shorthand call/cc. Any experienced Scheme coder is familiar with code like this:

(define (foo)

(let ([x (call/cc

(lambda (cont)

(display "captured continuation")

(cont 5)

(display "continuation called")))])

(display "returning x")

x))

(display (foo))

I implemented a callCC function in my special JavaScript variant since it already has all the necessary machinery. Additionally, we can use the stepping debugger to study how continuations affect the control flow.

function foo() { var x = callCC(function(cont) { console.log("captured continuation"); cont(5); console.log("continuation called"); }); console.log("returning x", x); return x;}console.log(foo());Output:

Stack:

This is a very simple example of using a continuation. Click "Run & Ignore Breakpoints" to see what happens. We capture the continuation using callCC, which gives us the continuation as the function cont. We then log "captured continuation" and invoke cont. Note how "continuation called" is never logged. Why is that?

Now go back and click "Run" to hit the breakpoint on line 13, and continually click "Step" to step through the program to see what happened. What happens when cont is invoked?

It jumps back to line 3! The previous control flow is aborted and the stack when cont was captured is restored. Any arguments passed to continuations replace the call to callCC, as if callCC returned that value. The continuation represents a state of the program where the callCC function is waiting to return a value.

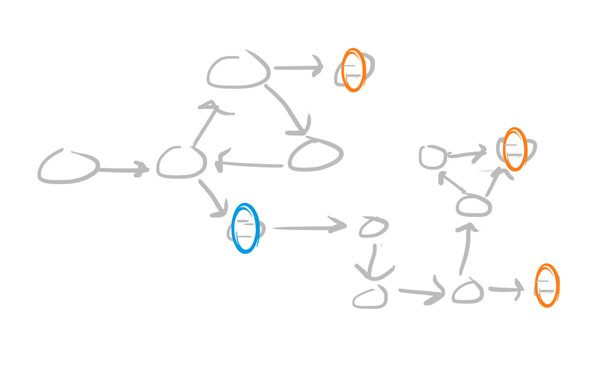

Continuations are like portals. If the image below represents your control flow, you can capture the current stack (the blue portal) and jump back to it at any time (the orange portals).

However, just like in the game Portal, these portals do not traverse time. The only thing that a continuation saves is the stack, so any changes to variables will still be seen after jumping through a continuation. Look at what happens with a closure:

function foo() {

var x = 5;

var func = function() { return x; };

x = 6;

return func;

}

console.log(foo()())

This will print 6 because closures reference the same variable that is mutated later. With continuations, it's the same thing except stack frames are pointing to the variables. We will show examples of this later.

Practical Uses

Now that you understand the general idea, let's put continuations to good use. This certainly seems powerful, but you might have trouble thinking of problems this solves. In fact, you might be thinking that this would just make programs harder to follow.

Abusing continuations definitely makes programs harder to follow. But there are constructs that continuations allow you to build that are generally helpful; break and continue might make your program a little harder to follow, but they solve real problems, just like other control flow operators. Additionally, in a future post we will talk about delimited continuations which force developers to use continuations in a clearer way.

The first exercise is to implement the JavaScript some method, which checks if any element in an array passes a predicate check. Importantly, it is "short-circuiting," meaning it stops iterating after finding the first passing element because it doesn't need to check the rest.

function some(predicate, arr) { var x = callCC(function(cont) { for (var idx = 0; idx < arr.length; idx++) { console.log('testing', arr[idx]); if(predicate(arr[idx])) { cont(true); } } return false; }); return x;}console.log(some(x => x >= 2, [1, 2, 3, 4]));Output:

Stack:

some using continuations.

If you run this, you'll notice that it doesn't check 3 or 4. It stops executing once 2 passes the predicate check. Step through the code and watch how it does that.

Of course, we could use break to stop the while loop. But this is a trivial example; it's common to call out to other functions within the loop where you can't break. The native control operators are quite limiting. Continuations, however, allow you to travel across stack frames.

For example, let's say you wanted to use forEach method instead of a for loop, because you already use that method everywhere else. Here is the example now:

// Note: don't use native forEach so you can step// into this onefunction forEach(arr, func) { for (var i=0; i < arr.length; i++) { func(arr[i]); }}function some(predicate, arr) { var x = callCC(function(cont) { forEach(arr, function(val) { console.log('testing', val); if(predicate(val)) { cont(true); } }); return false; }); return x;}console.log(some(x => x === 2, [1, 2, 3, 4]));Output:

Stack:

some using continuations across stack frames.

It works exactly the same way, even if we are calling the predicate within the function passed to forEach. It still short-circuits. Note how we didn't have to change anything about forEach; we are able to reuse the same method that we already use everywhere else.

This highlights a fundamental difference of continuations and anything currently in JavaScript: it suspends the entire stack. Generators suspend code as well, but their yield is shallow. It only suspends one frame, the generator itself.

While that makes code clearer, it leads to a proliferation of special syntax across all code and forces a lot of work on the developer over the lifetime of a project. Converting a single sync function to async requires a massive refactoring, changing the interface of every thing that uses it. I recommend reading "What Color is Your Function?" for a great description of this problem.

In the next post we will show how having a single function interface (no function* or async function) and deep stack control greatly improves the reusability and readability of code.

Exception Handling

Let's get real. The above exercises are pretty stupid. You wouldn't actually use continuations like that; there are much better constructs for looping over values and short-circuiting. Those examples were simple on purpose for illustrative purposes.

Now we will implement a new fundamental control construct: exceptions. This shows that continuations allow you implement things previously built-in to the language.

Users should be able to throw exceptions and install handlers to catch them. Installed handlers are dynamically scoped for a given section of code: any exception that occurs within a given block of code, even if it comes from an external function, should be caught.

Exception handlers must exist as a stack: you can install new handlers that override existing ones for a given period of time, but the previous ones are always restored once the newer ones are "popped" off the stack. So we must manage a stack.

The stack is a list of continuations, because when a throw happens we need to be able to jump back to where the try was created. They means in try we need to capture the current continuation, push it on the stack, run the code, and dispatch exceptions. Here is the full implementation of try/catch:

var tryStack = [];

function Try(body, handler) {

var ret = callCC(function(cont) {

tryStack.push(cont);

return body();

});

tryStack.pop();

if(ret.__exc) {

return handler(ret.__exc);

}

return ret;

}

function Throw(exc) {

if(tryStack.length > 0) {

tryStack[tryStack.length - 1]({ __exc: exc });

}

console.log("unhandled exception", exc);

}

The key here is that continuations can be resumed with values. The return body() line will return the final value of the code. At that point no continuation was invoked; it just passes that value through. But if Throw is invoked, it will call the captured continuation with an exception value, which gets assigned to ret, and we check for that type of value and call the handler. (We could do more sophisticated detection of exception types.)

Note that we pop the current handler off the stack before calling it, meaning that any exceptions that occur within exception handlers will properly be passed up the handler stack.

Here's what it looks like using Try/Catch:

function bar(x) {

if(x < 0) {

Throw(new Error("error!"));

}

return x * 2;

}

function foo(x) {

return bar(x);

}

Try(

function() {

console.log(foo(1));

console.log(foo(-1));

},

function(ex) {

console.log("caught", ex);

}

);

Unfortunately JavaScript does not allow us to extend syntax (although this can be solved with sweet.js macros, as we'll show in future posts). Instead of using blocks we must pass functions into Try. The output of this code would be 2 \n caught "error!".

The above implementation and example code are loaded into the editor below, with a breakpoint already set at the Try block. Hit "Run & Ignore Breakpoints" to verify the output, and "Run" to break and step through the code to see how it unfolds.

var tryStack = [];function Try(body, handler) { var ret = callCC(function(cont) { tryStack.push(cont); return body(); }); console.log('ret is', JSON.stringify(ret)); tryStack.pop(); if(ret.__exc) { return handler(ret.__exc); } return ret;}function Throw(exc) { if(tryStack.length > 0) { tryStack[tryStack.length - 1]({ __exc: exc }); } console.log("unhandled exception", exc);}// Example code:function bar(x) { console.log('x is', x); if(x < 0) { Throw(new Error("error!")); } return x * 2;}function foo(x) { return bar(x);}Try( function() { console.log(foo(1)); console.log(foo(-1)); }, function(ex) { console.log("caught", ex); });Output:

Stack:

x is -1 in bar, it will throw an exception which will be handled by our handler. Step through the code to see.

There are far more complicated control constructs that you can implement using continuations, and we will look into many future in a future post.

Calling from the Outside

So far we have always invoked a continuation inside the callCC call. That means we are always only jumping up the stack, meaning we're trying to jump back to a previous stack frame.

There's a name for these kinds of continuations: escape continuations. These are a more limited continuation that can only be called within the dynamic extent of the function passed to callCC (in this case it would be callWithEscapeContinuation or callEC). A lot of things like exceptions can be implemented only with escape continuations.

The reason for the differentiation is performance. Escape continuations don't need to save the entire stack and they can assume that the stack frames at the point of the callEC call will always exist in memory whenever the continuation is invoked.

However, my implementation of continuations is full continuations. This is where things really start getting mind-bending. In future posts, we will use this technique to implement features like coroutines. It's worth looking at a simple example for now.

Within the callCC call, you can just return the continuation itself:

var value = callCC(cont => cont);

value will be the continuation, but we don't name it cont because it will be different values later in time when the continuation is invoked. value will be whatever value the continuation is invoked with. We can make this easily reusable by wrapping it into a function:

function currentContinuation() {

return callCC(cont => cont);

}

Now we can do things like:

function currentContinuation() { return callCC(cont => cont);}function foo() { var value = currentContinuation(); if(typeof value === "function") { console.log("got a continuation!"); // Do some stuff var x = 5; value(x * 2); } else { console.log("computation finished", value); }}foo();Output:

Stack:

This is really powerful because it shows that we can invoke a continuation from any point in time, and it all works.

The above example is trivial, so in the spirit of attempting to show more value, here is a more complex example. This implements a very basic form of a coroutine that can pause itself and resumed with a value.

function currentContinuation() {

return callCC(cont => ({ __cont: cont }));

}

function pause() {

var value = currentContinuation();

if(value.__cont) {

throw value;

}

else {

return value;

}

}

function run(func) {

try {

return func();

}

catch(e) {

if(!e.__cont) {

throw e;

}

var exc = e;

return {

send: function(value) {

exc.__cont(value);

}

};

}

}

When a coroutine calls pause, the continuation is thrown, the scheduler catches it, and returns an object that gives the caller the ability to resume it. A very simple program that uses this:

function foo() {

var x = pause();

return x * 2;

}

var process = run(foo);

if(process.send) {

process.send(10);

}

else {

console.log(process);

}

The check for process.send is needed because our implementation is very naive. It saved the full continuation, which includes the top-level stack at the point when run is called. That means when the process is resumed, the top-level control is restored as well and we will see run return again.

Challenge: implement a version where process.send returns the final value instead of forcing the user to handle the return from run multiple times.

Here is the full program in an editor that lets you step through:

function currentContinuation() { return callCC(cont => ({ __cont: cont }));}function pause() { var value = currentContinuation(); if(value.__cont) { throw value; } else { return value; }}function run(func) { try { return func(); } catch(e) { if(!e.__cont) { throw e; } var exc = e; return { send: function(value) { exc.__cont(value); } }; }}function foo() { var x = pause(); return x * 2;}var process = run(foo);if(process.send) { process.send(10);}else { console.log(process);}Output:

Stack:

In future posts, we will look at more robust techniques for implementing coroutines with continuations.

Closing Over Data

It's very important to understand that continuations only save the call stack, not any of the data that stack frames may reference. Restoring a continuation does not restore any of the variables that those stack frames use. In this way, think of each stack frame as a closure that simply references those variables, and any external changes will still be seen.

This is confusing for beginners, but hopefully this is a simple illustration:

function foo() { var x = 5; callCC(function(cont) { x = 6; cont(); }); console.log(x);}foo();Output:

Stack:

6 because the change to x is still seen after the continuation is restored. Capturing does not save the value of x.

It doesn't matter when the continuation is invoked. If we saved the continuation for later, changed some local variables, and returned from the function, when the continuation is invoked it will still see all the local variable changes. A continuation closes over its data.

The Backstory

There's a long history here, but I'll keep it short:

In 2011 I worked on an in-browser game editor and I wanted the ability to interactively debug code.

Around this time I implemented my own Scheme-inspired language, Outlet, and tried to make it debuggable. I did it with a continuation-passing-style (CPS) transformation, effectively implementing continuations, but this forced me to re-implement stacks and scopes. It was very slow (can't compete with native JS stacks & scopes). I blogged the details here:

In an attempt to use native JS function scoping, I thought about abusing generators to suspend functions. While I still needed to re-implement the stack, at least variables are native and the implementation is much simpler (generators were just landing in JS engines). I called it YPS and it works by

yielding every single expression and running in a special machine. It was horrendously slow.In response to my generator-based suspension idea, @msimoni pointed me to the paper "Exceptional Continuations in JavaScript". I realized that what I wanted required all the machinery of continuations, and that paper outlines a technique to implement them without much run-time performance cost. Although capturing continuations is slow, all other code has a minimal perf hit.

That paper describes a really neat trick to implement continuations, which gives me the power to arbitrarily jump around code. Unfortunately it requires a sophisticated transformation, but right around this time regenerator came out which implemented a similar transformation! I forked regenerator, implemented continuations, got a stepping debugger working, and then realized that I could expose continuations first-class and be able to do all the things I'm about to show you. (That was around 2 years ago. This project sat on my computer for that time until I resurrected it a few weeks ago.)

Next: The Implementation Details

I was going to explore the implementation details in this post, but it's already so dense that I am pulling this out into a separate post. Check out the next post if you are interested in details!

Explore!

I think this is could be a fun playground for playing with various advanced control operators. I'm also pretty proud that I was able to get an in-browser stepping debugger working for interactive tutorials.

I will go into more advanced usages of continuations, particularly delimited continuations, in future posts.

If you are interested in this, check out unwinder!

JAMES LONG

JAMES LONG